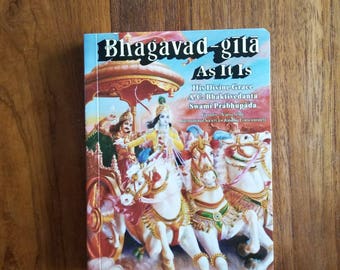

Bhagavad Gita Pocket Edition

Posted By admin On 25/06/18

According to Paramahansa Yogananda – Edited by his disciple, Swami Kriyananda Paramhansa Yogananda’s revelation of India’s best-loved scripture brought an entir. The Hardcover of the The Bhagavad Gita: Pocket Edition by Swami Nikhilananda at Barnes & Noble. FREE Shipping on $25 or more! Buy a cheap copy of The Bhagavad Gita book by Anonymous. The esteemed, poetic classic translation in a pocket edition. Published by Thriftbooks.com User.

Join our family of supporters.

The 'Song Celestial' is Sir Edwin Arnold's beautiful rendering of India's most beloved spiritual text, The Bhagavad Gita, and has been kept in print by the press of Yogananda's Self-Realization Fellowship. How To Lable A System 5 Plus Bontempi Keyboard on this page. This is a convenient, pocket-size hardback that is a joy to read from whenever you have a free moment.'

The words of Lord Krishna to Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita are at once a profound scripture on the science of Yoga (union with God) and a textbook for everyday living. The student is led step by step with Arjuna from the mortal consciousness of spiritual doubt and weakheartedness to divine attunement and inner resolve. The timeless and universal message of the Gita is all-encompassing in its expresssion of truth. The Gita teaches man his rightful duty in life, and how to discharge it with the dispassion that avoids pain and nurtures wisdom and success. Mfc71u.dll Missing Windows 2008. ' --Paramahansa Yogananda (from book jacket)Regarding the style of translation, Sir Edwin explains in his preface: 'The Sanskrit original is written in the Anushtubh meter, which cannot be successfully reproduced for Western ears. I have therefore cast it into our flexible blank verse, changing into lyrical measures where the text itself similarly breaks.

For the most part, I believe the sense to be faithfully preserved.' One definite quibble about the translation is made explicit in Yogananda's autobiography where he notes that virtually *every* translator of The Gita into English mistakes Krishna as instructing his disciples to meditate with the gaze focused on 'the tip of the nose.' Yogananda points out that the Sanskrit 'nasikagam' actually means 'source' or 'root' of the nose -- a reference to *the point between the eyebrows* - the 'spiritual eye'. For an esoterically sophisticated appreciation of such subtle (but vital) translation issues, you may want to turn to Yogananda's illumined commentary on the Gita: 'God Talks with Arjuna.' Juan Mascaro's edition of the Gita is undoubtedly one of the more attractive versions for the general reader who is approaching the Gita for the first time. Mascaro, besides being a Sanskrit scholar, is a sensitive translator who clearly resonates to the Gita. He tells us that the aim of his translation is 'to give, without notes or commentary, the spiritual message of the Bhagavad Gita in pure English.'

To suggest just how well he has succeeded, here is his rendering of Verse II.66:'There is no wisdom for a man without harmony, and without harmony there is no contemplation. Without contemplation there cannot be peace, and without peace can there be joy?' Many readers will probably be content to remain with Mascaro, and it certainly seems to me that his translation reads beautifully and that a fair number of his verses have never been bettered by others. But the Gita is not quite so simple as it may sometimes appear. If we want to arrive at a fuller idea of just what the Gita means by 'wisdom,' 'harmony,' 'contemplation,' 'peace,' and so on, we will need to consult other and fuller editions.There are many editions which, besides giving a translation of the Gita, also give a full commentary such as the excellent one by Sri Aurobindo in his 'Bhagavad Gita and Its Message' (1995).

Mutilate A Doll 2 Android on this page. Others, besides giving a commentary and notes, also give the Sanskrit text along with a word-by-word translation. Some of these even include the commentary of the great Indian philosopher, Shankara (c.

+ 788 to 820), such as the very fine edition by Swami Gambhirananda (Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama, 1995, which may be available through the Vedanta Press, CA). Here is the latter's English rendering of Verse II.66:'For the unsteady there is no wisdom, and there is no meditation for the unsteady man. And for an unmeditative man there is no peace. How can there be happiness for one without peace?'

This may not seem to have carried us much beyond Mascaro until we start looking at Shankara's commentary, of which the following provides a taste:'Ayuktasya, for the unsteady, for one who does not have a concentrated mind; na asti, there is no, i.e. There does not arise; buddhih, wisdom, with regard to the nature of the Self; ca, and; there is no bhavana, meditation, earnest longing for the knowledge of the Self; ayuktasya, for an unsteady man. And similarly, abhavayatah, for an unmeditative man, who does not ardently desire the knowledge of the Self; there is no shantih, peace, restraint of the senses. Kutah, how can there be; sukham, happiness; ashantasya, for one without peace? That indeed is happiness which consists in the freedom of the senses from the thirst for enjoyment of objects; not the thirst for objects - that is misery to be sure. The implication is that, so long as thirst persists, there is no possibility of even an iota of happiness!'